Tackling Wicked Problems in Higher Education

Dr. Jessica Riddell

Stephen A. Jarislowsky Chair of Undergraduate Teaching Excellence

Executive Director, The Maple League of Universities

Full Professor, Department of English, Bishop's University

3M National Teaching Fellow (2015)

Bishop's University

Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada

Traditional Territory of the Abenaki, members of the Wabenaki Confederacy

Former US Secretary of State George Shultz once drew a distinction between “problems you can solve and problems you can only work at.”

These two types of problems have names: they are tame or wicked.

Wicked problems are messy, confusing, unstable, ill-structured, and ambiguous.

The Maple League of Universities was originally created to solve a wicked problem. The wicked problem was a lack of awareness or understanding of quality undergraduate education in Canada.

Prospective students, parents, and policymakers were not, for the most part, able to articulate the differences in student experience between a large, comprehensive university compared to a small, primarily undergraduate, rural and residential university.

In contrast, the United States values diverse models of student experience, from small liberal arts colleges to large, state-funded universities. Furthermore, American universities have long recognized the value of collaboration through a consortia approach, whether that is driven by sports, like the Ivy League, regional interests and joint programming like the Five College Consortium, or through the delivery of innovative online courses like the newly founded League for Innovation in the Community College.

Canada tops the list as the most educated country in the world, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Universities Canada (2019) estimates that there were ~1.4 million students in Canadian universities in 2018: 77% were at the undergraduate level (CAUT, 4.8, 2019). Furthermore, undergraduate enrollment has increased 24% over the past decade (CAUT, 4.2, 2019). For the vast majority of students studying at Canadian universities, undergraduate education is the terminal degree.

Although recent polling by CAUT reveals that “most Canadians believe that it has never been more important to get a post-secondary education,” only 68% of first-year undergraduate students believe that university is worth the financial investment (CUSC 2019).

The cost of higher education, the future of work, and pressing social issues (climate change, poverty, income inequality, food instability, racism, gendered violence) exposes the need to deliver high quality, accessible 21st century education: we must equip new generations of thinkers to tackle wicked problems. The pressure has never been higher, and yet the wicked problem persists.

Students interested in studying at Canadian universities should be able to make informed choices about their undergraduate experience.

"Therefore, in 2012, four Canadian universities – Bishop’s, Acadia, Mount Allison, and St. Francis Xavier – decided to collaborate on this wicked problem. The first Canadian consortium of its kind, in 2016 they formed The Maple League of Universities with a mission to raise the profile of small, primarily undergraduate universities committed to quality 21st century liberal education."

When I assumed my role as Executive Director in 2018, I was inspired by the tremendous potential this collaboration could have on the higher education sector. As I write elsewhere, inter-institutional collaboration is no easy ask: universities are wired to compete when they recruit prospective students, compete against one another in athletics, and compete for funding in capital campaigns and external fundraising. Students compete for grades, academics compete for grants, and departments compete for resources.

In addressing one wicked problem – raising the profile of small, liberal education universities – the consortium created a new wicked problem, which was: how do we rewire our mindsets in order to think carefully and critically about how collaboration makes us all better than the sum of our individual parts?

Over the past three years we’ve made tremendous strides, including attracting over $1 million in funding for high-impact practices and experiential learning, building integrated hubs and innovation networks (across research, teaching, and professional clusters), mentoring students and faculty with national recognitions for educational leadership, and more.

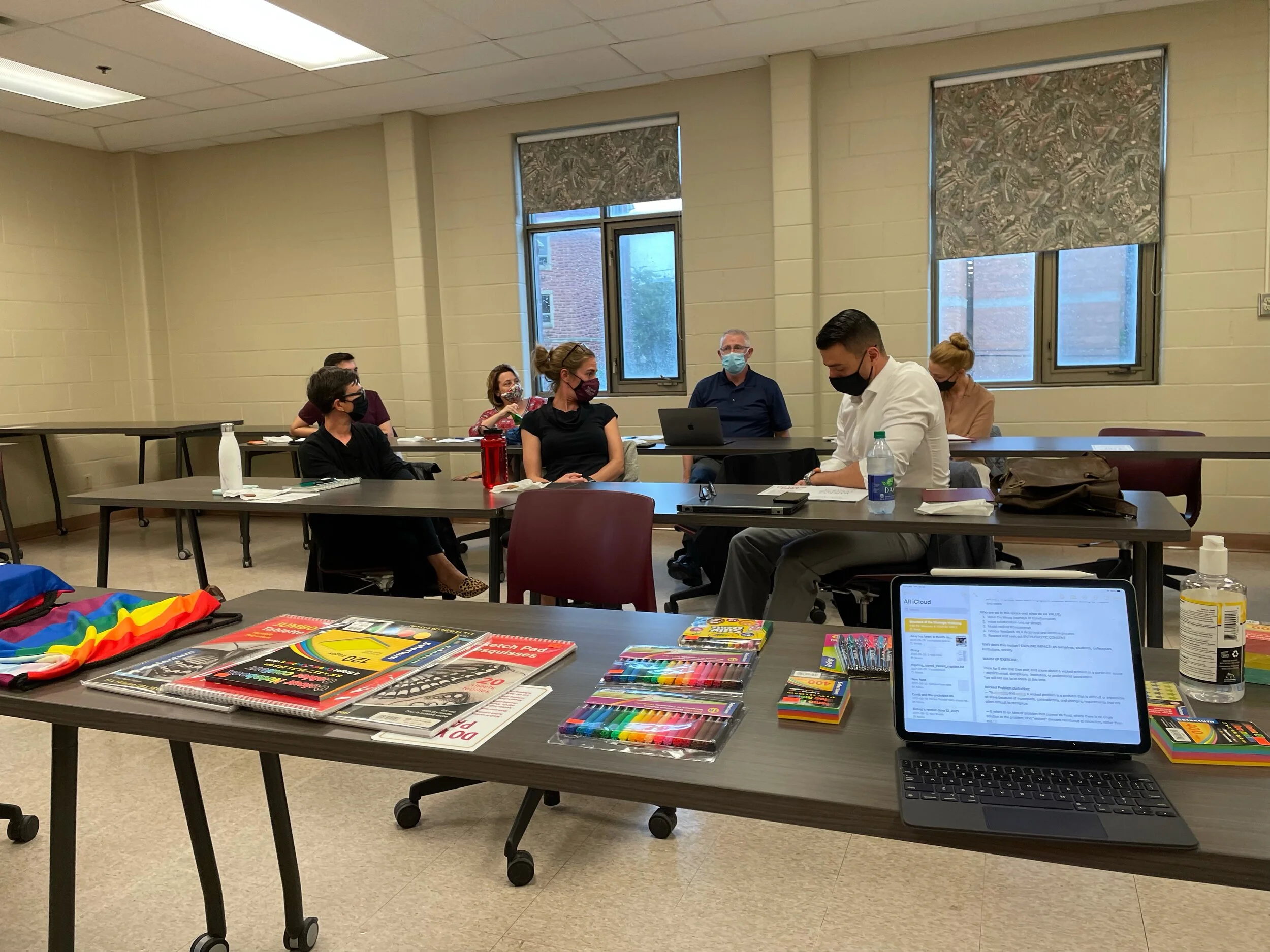

Maple League Teaching and Learning Committee Retreat (top) and Registrars' Retreat (bottom).

However, innovation and institutional change present tremendous challenges. The most disruptive interventions require us, as philosopher Ira Shor urges, to “challenge the actual in the name of the possible.” Disruption, therefore, does not occur without dissonance. The more disruptive the idea, the more likely it is “wicked,” complex, and creates significant disturbance.

To harness disruption in generative ways, I curated a series of wicked problem design principles to guide a new strategic visioning process for 2021 and beyond. These design principles help illuminate some of the challenges and opportunities we face. The concept of wicked problems is not new: Rittel and Webber coined the term in the context of problems of social policy in 1973. And yet, a renewed commitment to solving wicked social problems is essential to fulfilling the moral contract universities have to the broader society.

In the strategic visioning process I have distilled five design principles drawn from a broad range of theorists that I hope are flexible enough for diverse sectors and industries:

1. “A wicked problem is a problem that is difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize.” In other words, a wicked problem like climate change or income inequality is overwhelming and hard to even get into focus because the edges are blurry and the shape is constantly changing.

2. A wicked problem “refers to an idea or problem that cannot be fixed, where there is no single solution to the problem.”

This is a frustrating one for those of us who identify as “fixers” because there is no singular approach or narrow intervention. Instead, deep and meaningful impact can only be brought about when engagement is multi-pronged, distributed, combining a grassroots + top-down-supported approach. This means fostering integrated hubs and convergences across disciplinary and professional lines.

"We need individuals with different perspectives and experiences and expertise working collaboratively – including rethinking what counts as expertise and authority outside of traditional paradigms and structures. There are very few organizations who take this approach because co-design is messy and difficult and demands that we break open in order to transform."

3. "Wicked" denotes resistance to resolution, rather than evil.

While it is easier for us to dismiss something as evil, it is much harder to look at where the points of resistance lie and why resolution is difficult. As a Shakespearean, I love this formulation of “wicked”. In Act 4 of Macbeth the 2nd Witch says:

By the pricking of my thumbs,/Something wicked this way comes.

[Knocking] Open locks,/ Whoever knocks!”

[Enter Macbeth]

Macbeth is a truly catastrophic leader guilty of regicide, infanticide, civil war – but he starts off as a husband, a subject, a friend. Macbeth presents us with the wicked problem of tyranny and power and authority; by giving us the shape of the wicked problem Shakespeare helps us navigate our own current political landscapes at home and abroad.

4. Wicked problems are also characterized as having "social complexity [which] means that it has no determinable stopping point".

This means we are never going to get to a point where we can say, “we figured it out!” Instead, hope lies in the “ethical quality of the struggle” (Paolo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed). Tackling wicked problems demands that work is ongoing and ever evolving. Furthermore, progress is often really difficult to see – especially in the shorter term. When tackling wicked problems, we have to appreciate that change takes time, but that the hope lies in appreciating (not merely acknowledging) the complexity and the struggle.

5. If those four design principles aren’t challenging enough, a defining feature is that wicked problems beget more wicked problems: because of complex interdependencies, the effort to solve one aspect of a wicked problem may reveal or create other problems.”

This certainly has been the case in the Maple League, whereby the consortium was forged to tackle one wicked problem and exposed a series of other wicked problems in the delivery of accessible, inclusive, and high-quality undergraduate education.

One of the biggest wicked problems we did not anticipate was the global pandemic that shut down the world in March 2020. The rapid changes to our working and learning spaces challenged us to think about how we to live our fundamental values - of wonder and curiosity, respect for human dignity, knowledge and insight - in a world that has been radically disrupted.

COVID has moved our thinking forward in the use of technology, teaching and learning, equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility. We have had to harness technology to enhance what we do well – community, collaboration and transformative learning – in virtual, hybrid, and adaptable spaces.

In the midst of this disruption we’ve also returned to the fundamentals: we have come to appreciate, now more than ever, the value of face-to-face and immersive learning environments, the importance of peer-to-peer interactions amongst students, and the necessity of community-building and strong relationships to the citizen towns within which we are situated. We’ve had a stark reminder to value our time together because we know this time is precious.

Online Learning and Technology Consultants program at Mount Allison University (2021).

We’ve also learned that we can go farther together than we can on our own. The universities of the Maple League (Acadia and St. Francis Xavier in Nova Scotia, Mt. Allison in New Brunswick and Bishop’s in Quebec) – all rural, residential, primarily undergraduate, liberal education universities – doubled down on the collaborative approach in COVID, which has fostered resilience across our communities. By engaging with thought partners with similar challenges and hopes, we’ve been able to muster the energy to imagine a sustainable and resilient society.

Some pundits have predicted that the post-secondary sector will be predominantly online or virtual by 2030 – that it will never be the same. They are right that post-secondary education will not be the same after COVID-19, but not in the sense they imagine.

"If there is one basic conclusion that we should draw from our experiences managing the wicked problems the pandemic posed – from self-isolation to working from home, and hours of conference calls – it is that human beings need personal contact and direct interactions with others. Technology and effective pedagogical techniques have the potential to enhance post-secondary learning. We live in a global village which can be much more accessible through technology, even as technology also exposes the wealth gap and growing digital divide."

However, COVID-19 does not foretell the death of the classroom or the physical campus experience in Canadian universities; rather, it reminds us that direct personal interaction is a key component of education and the human experience.

Materials for visioning work at Mount Allison University (2021).

This model of collaborative engagement – in the classroom, within the university, and amongst the four institutions – represents values that are essential to maintaining a civil and just society.

John Dewey, American philosopher and educator, coined the term “creative democracy” in a speech he delivered in 1939 in response to the rise of fascism.

He posits that democracy is a moral ideal continually constructed through actual effort by people; he argues that “the present crisis is due in considerable part to the fact that for a long period we acted as if our democracy were something that perpetuated itself automatically.” Writing in 1939, Dewey’s insights are shockingly relevant to our current global climate.

Dewey concludes, “Since it is one that can have no end till experience itself comes to an end, the task of democracy is forever that of creation of a freer and more humane experience in which all share and to which all contribute.” Democracy itself is a wicked problem, always in perpetual motion and co-created through individual effort and collaborative spirit.

As I grapple with wicked problems, organizations like the Maple League that model collaboration over competition, and value complexity over singularity do not just show us what to do but rather how to be in the world.

The heart of this consortium is to encourage “inventive effort and creative activity” that Dewey believes is required to tackle the “critical and complex conditions of today.” I hope that the next time your thumbs prick because “something wicked this way comes,” you will have a framework for tackling some of our most pressing wicked problems.

For more information on the Maple League of Universities, please visit their website at www.mapleleague.ca .